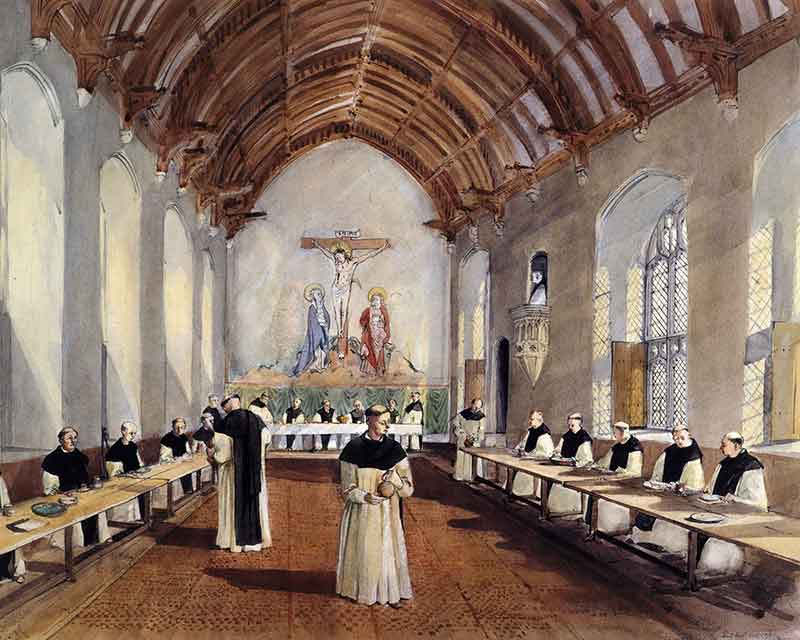

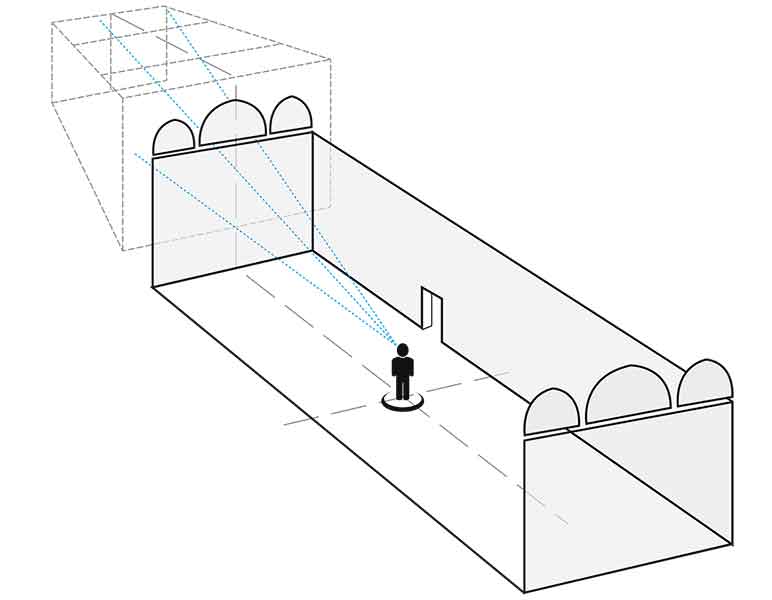

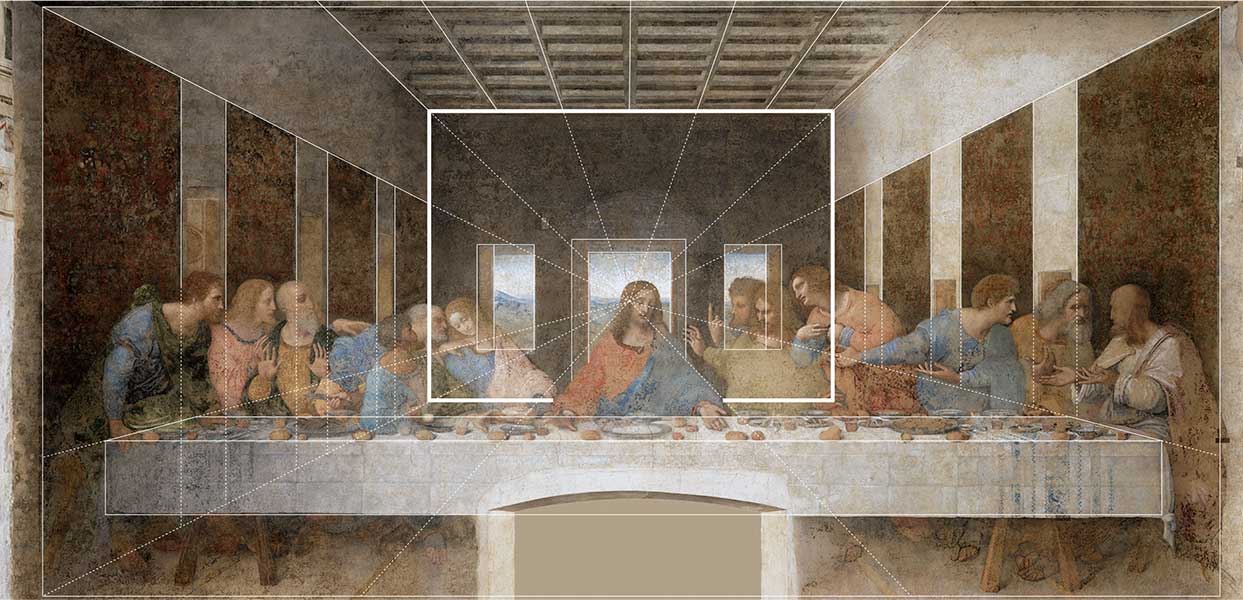

The refectory is rather like a perspective box in which the painted space and the real dimension interact.

This is why Leonardo chose to place the scene in a setting that can be described as open to the exterior and not in an enclosed space, unlike the traditional iconography.

The main light source is the windows set in the refectory’s left-hand wall

and this coincided with the light that illuminated the room in Leonardo’s day.

A slight effect of backlighting is also created by the large windows that we see in the background.

The presence of light sources enables these two dimensions

– the dimension of reality and the illusory dimension of the painting – to interact with each other.

The construction of the perspective, on the other hand, has its vanishing point at a height of four meters,

by Christ’s right temple.

To render the different planes of the painting, Leonardo used what he himself calls “aerial perspective” in his Trattato della pittura. He gives the example of mountains, which appear bluer in the distance, just as in the Last Supper.

The aerial perspective dear to Leonardo is represented here with an abrupt change in the chromatic range, passing from the warm colours of the figures in the foreground and the architectural space to cooler tones, such as green and blue, so conveying the impression of the air that lies between the eye of the viewer and the pictorial background.

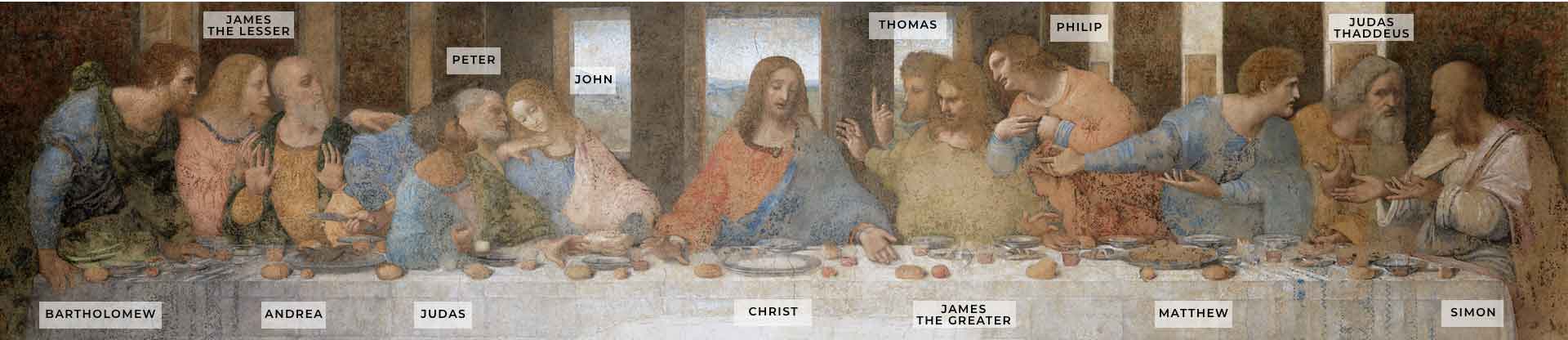

The first disciple on the left is Bartholomew, who is at the end of the table and seems to spring to his feet at Christ’s words. He rests his hands on the table and leans his body towards Jesus.

Near him is James the Lesser, whom we see in profile as he touches the shoulder of the older Andrew, who raises his hands as if to acquit himself of any suspicion of betrayal.

Next to him is Peter, whom his brother Andrew touches with his left hand as if to ask for comfort, but who is leaning towards John, the melancholy young man seated next to Christ.

Pietro seems to want to be sure of grasping Christ’s words as he urges John to ask the traitor’s name. Peter also holds a knife in his right hand, resting at his side.

Next to this group is Judas, who seems to shrink away from Jesus, while resting his elbow on the table. In his hand he holds the bag containing the 30 pieces of silver he received to betray Christ.

On the right, James the Greater throws open his arms in a gesture of disdain, while Thomas, leaning towards Christ, urges him to speak with the index finger of his right hand pointing upward.

Philip has just stood up and, facing Christ, he rests his hands on his breast with a grieving expression on his face.

Next to him is Matthew, who stretches his arms towards Christ. His face, however, is turned the other way, towards Simon and Judas Thaddeus, drawing their attention to the words they have just heard.

Judas Thaddeus, by contrast, is astonished. His left hand rests on the table with open palm, while with his right the apostle gestures towards himself.

Finally, Simon the Elder, with a more composed attitude, is seated at the head of the table, addressing Judas Thaddeus and Matthew.

Leonardo embodies a broad range of emotions in the expressions of the faces, gestures and attitudes of the bodies of the apostles:

they include anger, fear, amazement and sorrow because, as he himself wrote,