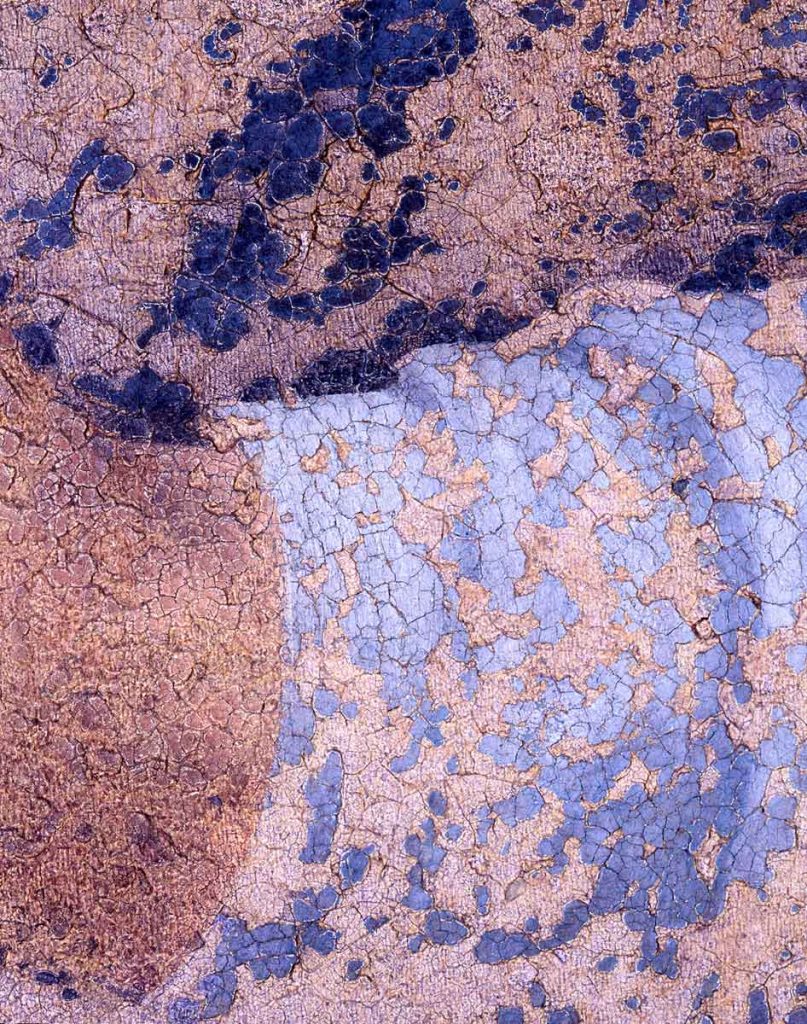

Leonardo painted the Last Supper using a dry technique: he applied the pigments to a white preparatory layer, which served to level and smooth the wall, instead of painting directly on the wet plaster. Hence the colours were not absorbed by the plaster, but rather superimposed on the wall. This made the painting much more vulnerable and fragile than fresco. This technique and the far from perfect environmental conditions caused the loss of pigment in the years immediately after the painting was completed. It also led to numerous attempts at restoration that over the centuries ended up by disfiguring its appearance and further harming its state of preservation.

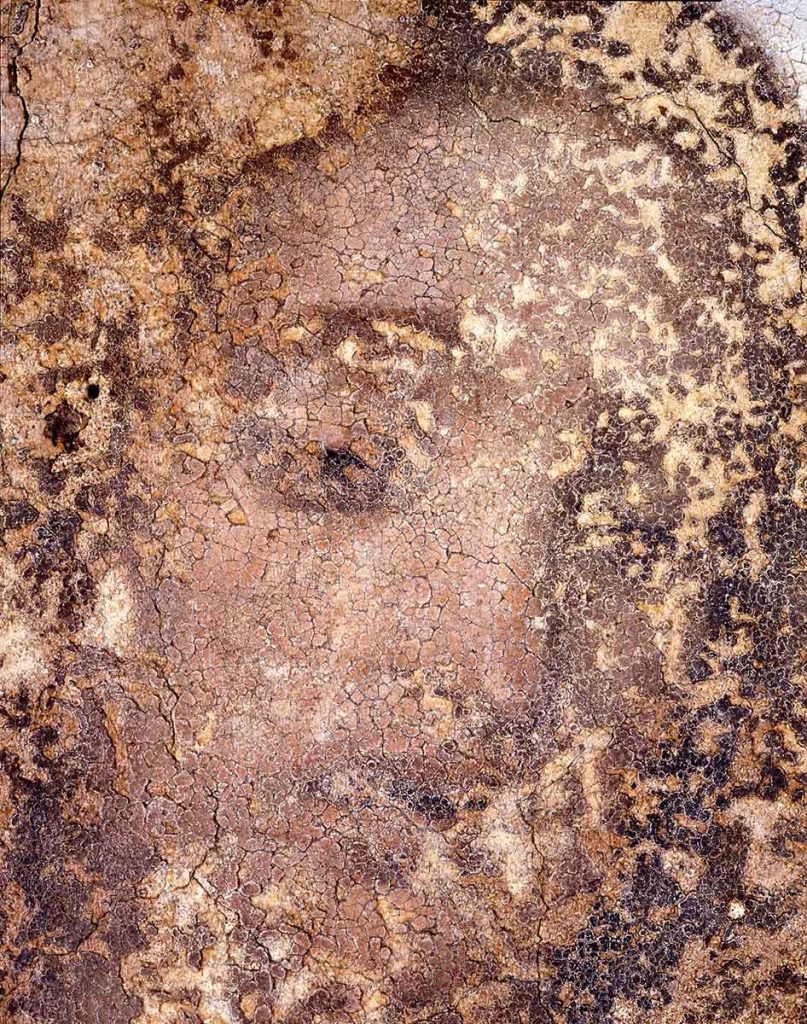

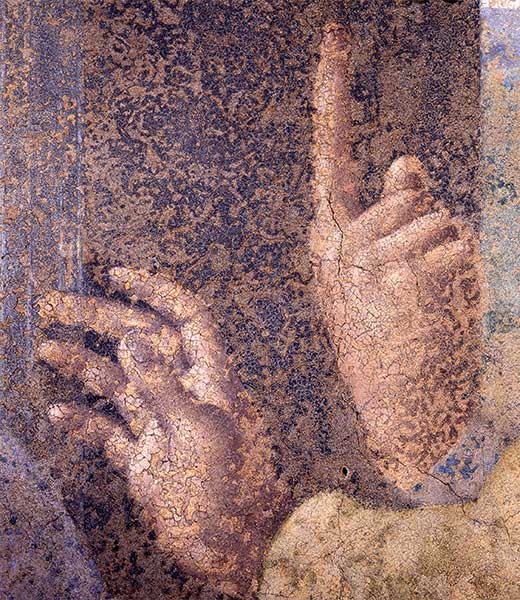

Leonardo da Vinci, the Last Supper, 1494-1498, detail of Christ during the restoration by Pinin Brambilla Barcilon, 1977-1998. Milan, Cenacolo Vinciano Museum. © Mic – Direzione Regionale Musei Lombardia

Leonardo da Vinci, the Last Supper, 1494-1498, detail of Matteo during the restoration by Pinin Brambilla Barcilon, 1977-1998. Milan, Cenacolo Vinciano Museum © Mic – Direzione Regionale Musei Lombardia

For this reason, after the last major restoration work completed in 1999, measures were taken to prevent it from deteriorating further. The air quality is carefully controlled in the refectory, consequently only small groups of visitors are allowed inside, while the environmental factors are continuously monitored: these are some of the measures adopted to ensure the work’s preservation. Hence the painting can only be viewed by appointment, with a limited number of people and restricted viewing times in the refectory. An uncontrolled influx of visitors would lead to an excessive increase in both relative humidity, with increased condensation of water vapor, and particulate matter. For these reasons access has to follow a path divided by automatic doors that close and open alternately. This allows a first natural filtering of the air that enters from outside, rich in pollutants that might harm the painting.

Leonardo da Vinci, the Last Supper, 1494-1498, table detail during the restoration byPinin Brambilla Barcilon, 1977-1998. Milan, Cenacolo Vinciano Museum. © Mic – Direzione Regionale Musei Lombardia

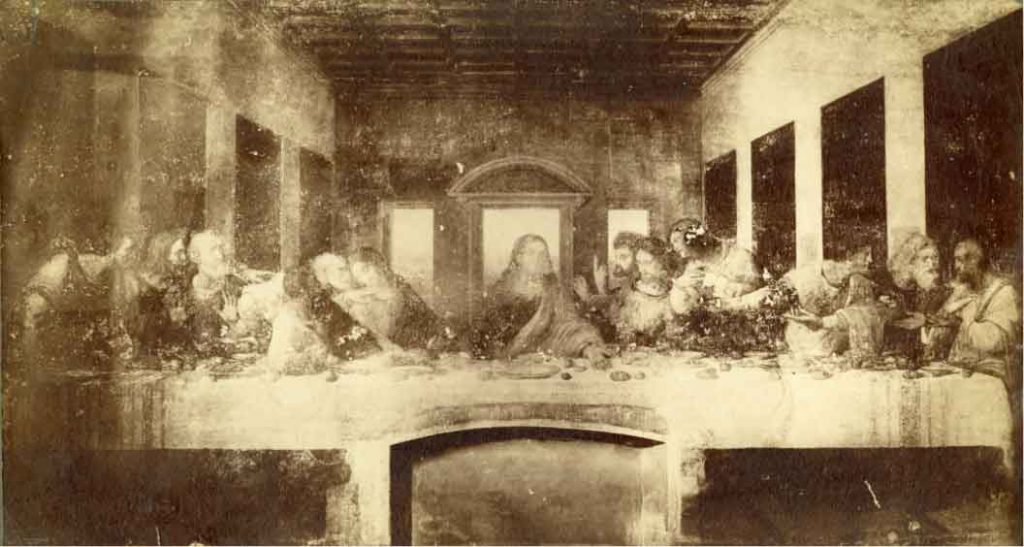

The Last Supper, 1901 ca (catalogo Anderson)

The image we see today offers only a faint memory of the masterpiece that could be admired by Leonardo’s contemporaries. Little is left of the original painting. The historical sources report that it had suffered considerable damage already a few years after its completion. In 1517 the canon Antonio De Beatis affirmed that the Last Supper “is beginning to decay”. In 1568 the artist and biographer Giorgio Vasari wrote that “we cannot make out anything more than a glowing stain”, badly blurred, and in 1625 Cardinal Federico Borromeo spoke of “falling flakes of paint”.

Clearly the Last Supper began to deteriorate a few years after its completion.

Leonardo did not use the traditional fresco technique to paint the Last Supper and the lunettes. He chose a method that would enable him to paint on dry plaster and work slowly, so as to be able to make changes to what he had already completed and lavish care on every least detail, working simultaneously on the whole surface of the painting. Fresco technique, on the other hand, requires the artist to work rapidly and does not allow for subsequent alterations, because the painter has to work on portions of plaster while it is still damp. Once it dries, no changes can be made. So this technique was poorly suited to Leonardo’s slow and meticulous approach, working with layer upon layer of paint.

The Last Supper after Luigi Cavenaghi’s restoration, 1908

In the Last Supper the artist painted on the wall as he would have done on a wooden panel, using greasy tempera made by mixing the pigments with egg yolk. This painting on dry plaster (called “a secco”) enabled him to create intense tones and refined effects of light.

Since the early 18th century, we have records of nine attempts at restoration of the Last Supper, although traces of similar earlier intervention have been found. In the past, however, restoration was understood as reconstruction and completion of the missing or decayed parts. For this reason it often involved repainting whole portions of the work. But by the 20th century, restoration was limited to preserving and consolidating the work with its gaps.

The church and the refectory of Saint Maria delle Grazie after the allied bombing on 1943. © Mic – Direzione Regionale Musei Lombardia

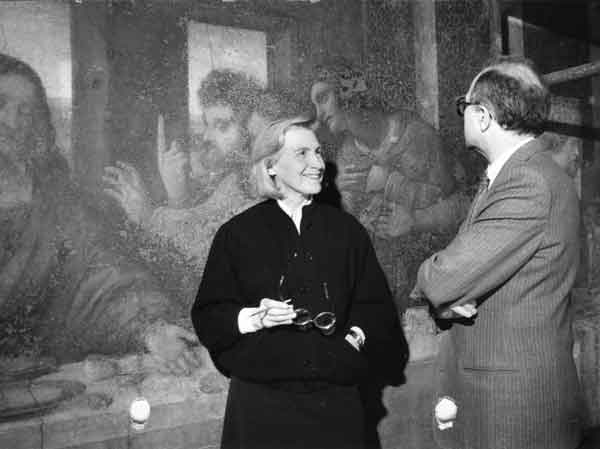

Pinin Brambilla Barcilon working on restoration of Leonardo da Vinci’s Last Supper, 1982. © Mic – Direzione Regionale Musei Lombardia

Mauro Pellicioli and the Last Supper. The making of of the film “Il miracolo della Cena. Le vicende del capolavoro di Leonardo da Vinci”, by Luigi Rognoni, Rizzoli film, 1953

Pinin Brambilla Barcilon and Carlo Bertelli working on restoration.

The last operation by Pinin Brambilla Barcilon, lasting over twenty years, from 1977 to 1999, for the first time sought to recover the parts painted by Leonardo, concealed by earlier overpainting, and restored to public view a work as close as possible to its original appearance.

Leonardo did not use the traditional fresco technique to paint the Last Supper and the lunettes. He chose a method that would enable him to paint on dry plaster and work slowly, so as to be able to make changes.

From Tuesday to Sunday:

from 8.15 a.m. to 7 p.m.

(with last admission at 6.45 p.m.)

To guarantee everyone a safe visit,

in this first experimental phase,

the visits last 15 minutes for

a maximum number of 35 people at a time

Reservations are required.

Reservations* for the Last Supper Museum will open every three months.

(*On Tuesday, June 17, starting from 12:00 p.m., admissions for August, September and October 2025 will go on sale through the usual purchasing channels)