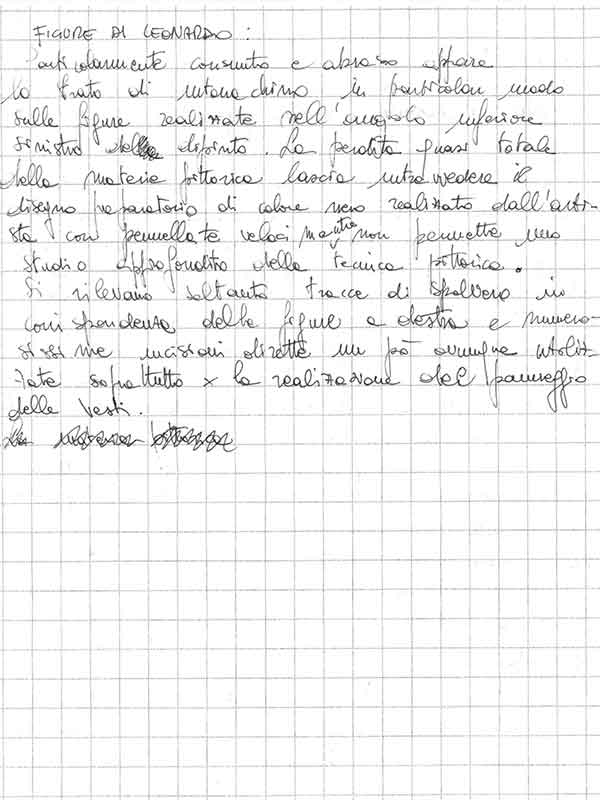

6. Fresco and dry techniques, metal foil

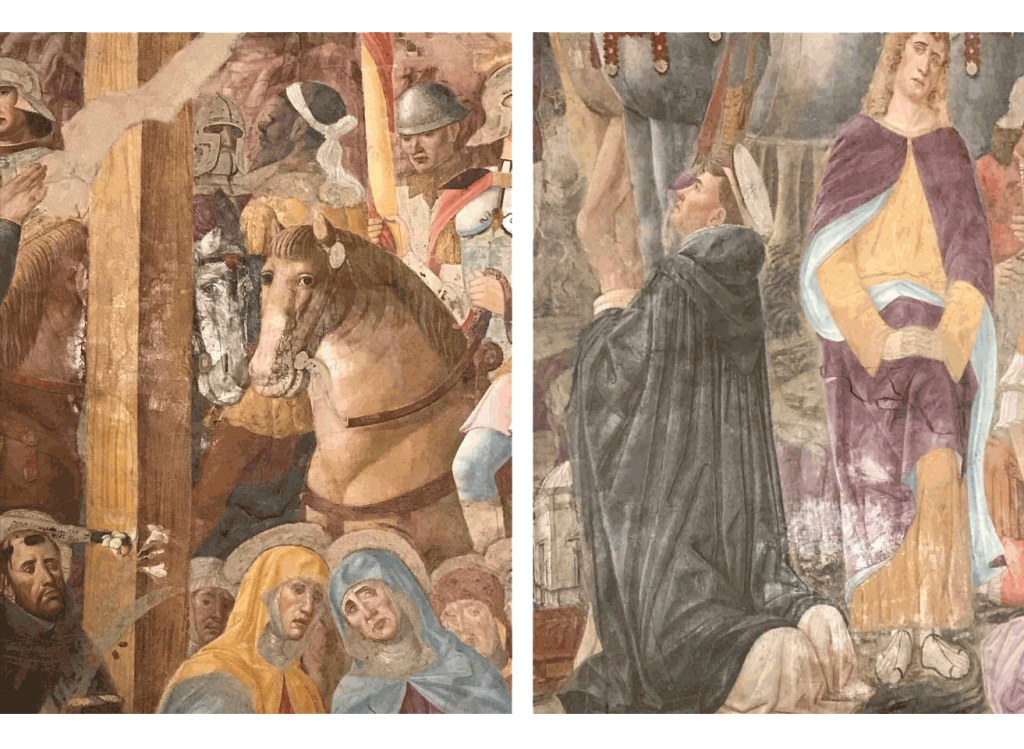

Close observation of the Crucifixion made it possible to identify not only the “days” of work (more than forty have been identified) but also the different techniques used in the execution, which includes parts applied in true fresco and others using a dry technique.

The term “dry” refers to the application of paint to dry plaster, with pigments mixed with various binders, some organic (casein, egg white, oil), others mineral (lime).

The combination of different techniques should not be interpreted as an error by the artist surprised by the unexpected drying of the plaster: in this case he would have replaced the portion of the dry surface with the damp “fresco plaster”. The change from one technique to another was planned from the start, to create particular effects or meet to the needs of pigments that are altered by contact with lime plaster. This is clearly explained in the Libro dell’Arte, the famous treatise that the painter Cennino Cennini wrote in the early 15th century, illustrating the main techniques used by artists in his day and a fundamental source-book for us.

Montorfano’s technique is consistent with the general information contained in the treatise, but above all with the traditional Lombard predilection for a rich, textured painting with a varied surface.

In Montorfano’s painting, for example, almost all the helmets and armour of the knights, as well as other details, like the tips of the spears and the bucket of the man at the foot of the cross, are not only modelled in relief, but have traces of metal foil.

This is almost certainly made of tin, now oxidised and dark, applied with the “mordant” system, which uses an oleo-resinous (mordant) adhesive mixture which could be of different colours, from white to red.

The metal foil was added over the finished paint, when the mortar was perfectly dry, and made to adhere with the mordant. Apart from tin, as in this case, the metal foil might also be silver, which oxidises even more rapidly (as Cennino wrote “it does not last and turns black”), or gold. Naturally this was reserved for the haloes and studs and embossed decorations on horse harnesses.

In the Crucifixion, gold was used to embellish the hems of the robes, the mouldings and capitals that define the lunettes, and the fabric of the banners. Unfortunately, all trace has been lost of the gilding that adorned the edges of Christ’s robe, the garments of the soldiers playing dice at the foot of the cross, the mantle of John and of the pious woman supporting the Virgin Mary.

We can now only see it in negative, from the traces left by the mordant and the gaps in the background colour.

But close study of the work has revealed many other details of the execution of the Crucifixion. Would you like to see which ones? Follow our next updates.